Description

Publication date: 2010

Editorial

Karim Basbous

Read moreFor Luis Barragan, Alvar Aalto, and Johann Otto von Spreckelsen, work on a project was a personal, patient, autonomous activity. Spanish architect Ignacio Mendaro Corsini belongs in this tradition of architects who devote their energies fully to the design and implementation of their work and waste no time on public relations.

Readers of this issue of Le Visiteur will be introduced to buildings that are a faithful reflection of their creator: dignified, calm, and self-assured, reticent at first sight but welcoming on further, deeper acquaintance. The dossier devoted to Mendaro Corsini opens with an article by Judith Rotbart and Laurent Salomon, who recognize the foundations of a specifically Castilian architectural modernism through an analysis of the Cheles school in Badajoz. The other essays, by Aurora Cappai, Olivier Gahinet and myself, Pascal Quintard Hofstein, and Philippe Rivoirard, all discuss the municipal Archives building in Toledo completed by Mendaro in 1998.

The second part of this issue focuses on the subject of “territoire,” with a group of essays first presented at a conference organized by the Société française des architectes and the CNRS.[1]

Pierre Caye introduces the concept of “dispositif” or deployment to make sense of contemporary production in urban and suburban contexts, and seeks to explain how this concept differs from that of the project. He investigates the origins and the power of a system that supports the unfettered, unlimited expansion of this type of space with no projectual or formal element. Bernardo Secchi rejects the technocratic urbanism mired in an analytic perspective that is no longer of any use to it: as a historian he examines the history of cities, as a geographer he analyses their configuration, as a sociologist he studies the human behavior they exhibit, never forgetting that a “territoire” is a living entity not reducible to abstract grids and statistics. His analyses are those of a practitioner who is also a theorist: they are inextricably linked with the resulting proposals for making major European conurbations more livable. Continuing the research he has been pursuing for a number of years on computers and architecture, Antoine Picon here describes three major characteristics of a city in which the development of information technology has unsettled some of the old points of reference in the reading and organization of space, and also presents the architectural project with new possibilities for action. My own piece asks whether the urban project is possible at all, if by that we mean not something located on a particular site, but a spatial quality that the current cultural context and the administrative requirements of professional practice may lead us to relinquish, and that only the force of will of the architectural project can save.

Two other contributions fill out this issue. Hashim Sarkis argues that the concept of geography is a more effective paradigm than the traditional categories for explaining the relationship of the architectural project to its context. Lastly, Pablo Pschepiurca’s analysis of Le Corbusier’s Buenos Aires project reinterprets it for us not as an incomplete city plan, an ideological gesture, but rather as an open-ended work, a porous deployment, still unfinished, available to inform future developments.

[1] “Le territoire dans tous ses états,” a conference organized by the Société française des architects and the CNRS, November 13-14 2009, with the support of the University of Paris-Est-Marne-la-Vallée and of the Urbaine de travaux.

Translated from the French by Linda Gardiner

The strategy of secrecy

Judith Rotbart and Laurent Salomon

Read more“One side of this wall, facing the viewer frontally, reveals the sun’s color; the other side is always shrouded in shadows, suggesting absent presences who seem to await their call to enter the stage.”

Emilio Ambasz

Beginning of the article…

Ignacio Mendaro Corsini’s buildings embody the current Iberian fondness for a critical form of modernism, a modernism that reinstates the wall as one of the subjects of contemporary architecture. The influence of Basque sculptors Oteisa and Chillida – lionized as the muses of architecture – is often identified as an explanation for the return to the Mediterranean roots of Spanish architecture, an architecture that keeps its wonders hidden deep within the project. However, we should not see this trend as a mere matter of formal proximity: this quest is something more than the pursuit of a predetermined aesthetic outcome. Le Corbusier’s Dom-ino house in its day helped lay the foundations of a theory of the independent existence of structure and envelope. This theory fueled a dogmatic “excommunication” of the wall from architecture. In Spain, this is no longer the case. The wall is there in all its substantial opacity.

We interpret this return to the wall as a desire to disconnect the issue of context from the issue of function. The point is not to return to the ontological functionality of modern architecture, but to offer a different way of resolving the competing claims of a building’s context and its social purpose. With respect to a building’s exterior, making an architectural form opaque redefines it as an event in the landscape, leading the viewer to perceive it on that scale. It no longer expresses its content directly, but presents itself as an entity within a context; it complements, reorganizes, or reinterprets an existing situation in a process often described as integration into the site. In the interior, where it is no longer dominated by the external Other, function itself develops, matures, and takes shape within the project. It seeks its own light, creating a private landscape in which it invents its own horizon, keeping it secret from its external surroundings. It is self-created, with no context, a free function. This other landscape, neither outside nor inside, that is the outcome of this strategy raises a theoretical question that concerns the very essence of modernity.

Toledo and its Archives

Aurora Cappai

Read moreStructure of the article…

The site

“The person to be painted stands before the artist like a world to discover,”[1] claimed Benedetto Croce. The same could be said of the site, which stands before the architect like a world to discover. The city of Toledo has a rich historical heritage. Its strategic position has meant that it has always had a major administrative, economic, and military role. It has always been able to defend itself against the successive conquerors who have appeared in the region over the millennia: Toledo was “a small but strongly fortified city,”[2] wrote Livy.

The time of the project

Visiting the Archives

[1] Benedetto Croce, Aesthetic as Science of Expression and General Linguistic, trans. Douglas Ainslie, New Brunswick, Transaction Publishers, 1995, p. 40.

[2] “Toletum ibi parva urbs erat, sed loco munito”: Livy, Ab urbe condita, Book 35.

A boon for scholars and sightseers

Stone archives, paper archives

Karim Basbous et Olivier Gahinet

Read moreBeginning of the article…

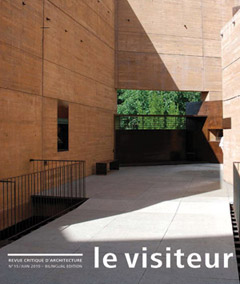

Designing a building for the center of Toledo to house the municipal archives meant implementing a major, high-value project for the city, but one that few actually visit except for scholars and sightseers. It was, in a sense, to be a public building without a public. This paradox was to nurture the project in several ways: in the way the building presents itself to the surrounding city, the way visitors enter it, and in the character of its interior spaces.

Luminous depth

Pascal Quintard Hofstein

Read moreBeginning of the article…

Best known for his drawings, Woods constructs a pictural realm, between comic strip and piranesean worlds: monolithic landscapes, deep canyons, alien neighbourhoods. The architect draws vertical spaces where sometimes natural light springs from deep abysses from where no one can decipher the source.

The architect and the well

Philippe Rivoirard

Read moreBeginning of the article…

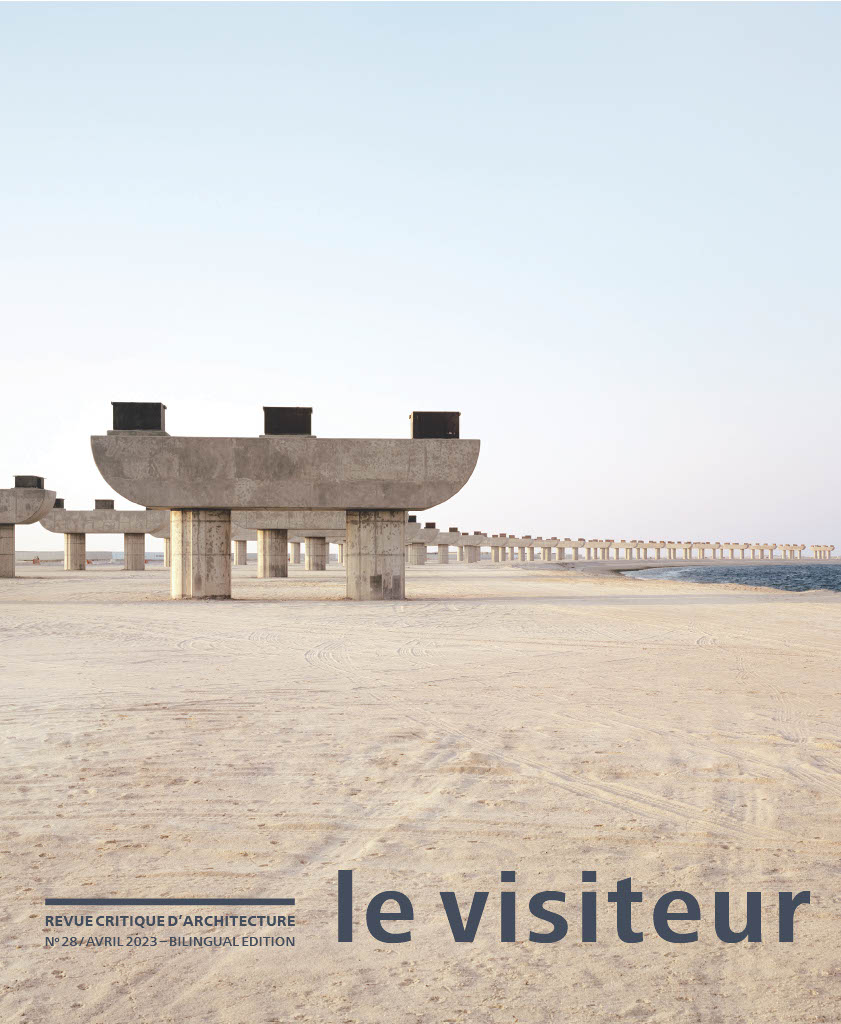

At the corner of one of the streets of Toledo you come upon a plaza, a wall, an opening, an entrance, a door. Nothing too forceful, but a plain statement; sobriety and mannerism, high-quality construction and well-chosen colors.

Once you go round the end of the wall, overlooked by a little corner window, a courtyard gives access on one side to a function room set up in an old church and on the other side to the city archives. In this courtyard, around the bases of four lobed pillars, a metal bench, ashtray, and podium seem to be conversing with one another.

The city between deployment and project

Pierre Caye

Read moreBeginning of the article…

Contemporary urbanism seems to confirm Quatremère de Quincy’s definition of architecture as an art with its feet on the ground and its head in the sky.[1] But the nature of both earth and sky in architecture today is obviously quite different from what it was in the age of classical or neoclassical architecture. The ground no longer means the location of the construction site and foundations, nor is the sky the sphere of just proportion and harmony. Architecture and urbanism still have their cosmological side, but human cosmology, like the celestial variety, has profoundly changed since the days of Quatremère. The “urban” ground is packed with rhizomes, networks of infrastructure, and exalted by an aesthetics of the festival, special or even unique events that emerge from those networks in a random, ephemeral fashion to form a new celestial vault for us to admire. What is missing from this cosmology is any sense of an intermediate sphere, between heaven and earth, where architecture as such (something that is neither infrastructure nor spectacle) has its natural place.

The lack of a place midway between earth and sky promotes the proliferation of networks at the terrestrial level and events at the celestial one. This proliferation, in turn, explains the confusion of the city and the break-up of the urban unit on both the geographical and theoretical levels. One of Pascal’s Pensées comes to mind – and in this context we may recall his contempt for everything that belongs to the realm of mere diversion, such as the baroque spectacles which our own century has inherited the taste for:

“A man is a substance, but if you dissect him, what is he? Head, heart, stomach, veins, each vein, each bit of vein, blood, each humour of blood? A town or a landscape from afar off is a town and a landscape, but as one approaches it becomes houses, trees, tiles, leaves, grass, ants, ants’ legs, and so on ad infinitum. All that is comprehended in the word ‘landscape’.”[2] This section of the Pensées is titled “Poverty”: the poverty of a reality that is unable to access order, coherence, and unity, the poverty of thought that is doomed never to attain them because “bad infinity” is constantly breaking reality up into little pieces.

[1] Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy, Encyclopédie méthodique d’architecture, I, Paris, Panckoucke, 1788, p. 110.

[2] Pascal, Pensées, fragment 65, trans. A. J. Krailsheimer, London, Penguin, 1995, p. 18.

A new urban question (1)[1]

Bernardo Secchi

Read moreBeginning of the article…

In recent years I have had the opportunity, in collaboration with Paola Viganò, to study a number of conurbations: the Veneto, a “dispersed city” which is where our research into urban sprawl began; the Antwerp region, the heart of a vast dispersed conurbation which extends from Lille to Brussels, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, and Cologne; and lastly Greater Paris, an agglomeration of twelve million people centered on Haussmann’s Paris, that “icon of the nineteenth century”. To these conurbations we can add others we studied more briefly, in Europe, Latin America, and China.

In each case the purpose of our study was the construction of a project, in the awareness that the project produces its own kind of knowledge whose character and epistemological status are both complex. This knowledge is independent of that produced by traditional urban analyses.[2] Through these project studies, we reached the conclusion that we are now, once again, faced with an “urban question”[3] which has led us to advance a number of hypotheses.

[1] I number this essay “I” because in November 2009 I gave three lectures with the same title, “A new urban question,” in Paris (SFA), in Zurich (ETH), and again in Paris (ESDA). The content of the three lectures was of course different. The first one, given in Paris, is reproduced here, and deals especially with the research pursued by Paola Viganò and myself in recent years in several European metropolitan areas, in particular Greater Paris. The second, given in Zurich, dealt especially with the issue of what further research is called for by the new urban question; the third, back in Paris, discussed the primary “metaphors” that have accompanied the “urban question” throughout its history. Bernardo Secchi, “A New Urban Question II,” The Swiss Spatial Sciences Framework (S3F), Zurich, November 18 2009; Bernardo Secchi, “A New Urban Question III: When, Why, and How Some Fundamental Metaphors Were Used,” École spéciale d’architecture, Paris, November 28 2009.

[2] Paola Viganò, Il progetto come produttore di conoscenza, Roma, Officina, 2010.

[3] I say “once again” because the urban question has arisen several times during the course of European history. In the eighteenth century it took the form of a polemic against luxury (Fenelon), and the place where capitalist accumulation first appeared; in the mid-nineteenth century it was focused on the housing problem (Engels), and the shift from handwork to the factory; in the late nineteenth century it centered on the “Grossstadt,” the emergence of the “crowd” and of mass society (Tarde, Le Bon, Park, Simmel, Kracauer, Benjamin); in the twentieth century, between the wars, it was the appearance of Fordism and universal mechanization (the urban utopias of Le Corbusier, Wright, the Disurbanists); in the 1960s (with Castells, Lefevre, de Certau) we witnessed the end of Fordism and the beginning of the ecological crisis. Each time the mode of production has changed, and with it the relationship between different social classes, another urban question has emerged. This topic has been more fully developed in Bernardo Secchi, “A New Urban Question II and III.”

The digital city: a new space for the project

Antoine Picon

Read moreStructure of the article…

Three potential characteristics of the city of tomorrow.

A city of individuals.

Architecture and augmented reality.

The city as event and architecture as performance.

The city’s debt to the project

Karim Basbous

Read more“What we simulate does not exist; what we dissimulate does exist.”

Torquato Accetto

Beginning of the article…

“Stadtluft macht frei”: The air of the city is liberating. I begin with this German aphorism which, though well over five centuries old, still admits of new interpretations. While this maxim does not have the force of an axiom, we may at least adopt it as a credo, one that the project can put its faith in. At a time when an unprecedented level of urban migration has seen more than half the world’s population move to live in cities built in accordance with the dictates of the market, we are entitled to ask how the architectural project – meaning the desire for transformation imbued with values that are not those of the market – can be pursued on a terrain that manifests itself as political, economic, and cultural cash. Is the city no more than a demographic and economic unit, or might we see in the necessary proximity of buildings, spaces, and uses the possibility of a form of friendship, the opportunity for a project that saves the building from mere individuality?

Le Corbusier’s vision for Buenos Aires: masterplan or manifesto?[1]

Pablo Pschepiurca

Read moreBeginning of the article…

Between October 1937 and 1938, Jorge Ferrari Hardoy and Juan Kurchan outlined a masterplan for Buenos Aires (hereinafter referred to as “the Plan”) under the direction of Le Corbusier. To this day the Plan has yet to be accorded the consideration it deserves, chiefly owing to political impediments and its perceived technical limitations, but also due to the physical scattering of the documentation and the aborted publication of Le Corbusier’s book on Buenos Aires.

The “failure” of the Plan has been attributed to the limitations of the urban development ideology of the CIAM (Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne) and to the authors’ wilful imposition of set formulas on a supposed tabula rasa. Another viewpoint, which, all things considered, is not all that different, presents it as a success, arguing that many of its proposals were actually implemented later on. In our opinion, the Plan was neither a laboratory exercise nor a set of seminal premonitory ideas, but a project combining several different goals.

[1] The following paper draws on a research project on Le Corbusier and his Argentine pupils, published in La Red Austral (Argentina: UNQ, 2008), by Jorge Liernur in collaboration with Pablo Pscherpiurca.

A Question of Geography

Hashim Sarkis

Read moreBeginning of the article…

Context

Increasingly, the term “geography” is being used to imply the total of externalities related to site, be they larger context, climate, landscape (landscape is still considered an externality), and social and economic setting. The term also stands for a general synthesis between the physical and social characteristics that make the site of action distinguishable from others. It is a synthesis that architecture aspires to provide. As the categories of designation of context such as city or suburb, or even a subcategory, become less tenable, the term geography is increasingly being used to describe a condition of flux or to register dissatisfaction with the categories that we still allocate to place.[1]

[1] The deference to geography, as a set of socio-physical phenomena and as a discipline, is not new. For Patrick Geddes, geography provided the underlay for his “valley section” model of human settlements. Architects have often based their assessments of setting on geography, relying on its ability to outline and validate the link between the social dimension of the urban artifact and their formal analyses. Today Mike Davis, David Harvey, and Edward Soja are required reading in architecture schools. The non-place that much of contemporary architecture seems to emphasize is in itself linked to these geographers’ astute descriptions of the ubiquity of placelessness in an increasingly globalized world.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.