Description

Editorial: The Modern Elan

Karim Basbous

DisplayFor Baudelaire, modernity is “the transient, the fleeting, and the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being the eternal and the immutable”. Words are lasting; their meanings evolve. Of few words is this more true than the adjective “modern”. What does it mean in terms of today’s architecture? The Modernist movement made use of the concept to frame a set of new departures that broke with architectural convention. What has the term come to mean since? How and why has this important word come to seem like an insult to so many architects? By what strange twist did a word representing the future come to be associated with the past? Is the modern élan now consigned to history, or on the contrary, is it a dynamic school of thought whose potency lies in its continual renewal? This is the debate we hope to spark. My own interest is in modernity not as an attribute of the built form, but as the intellectual stance by which the mind allows itself to indulge in an unusual, subversive degree of freedom, contrary to the “schools” that institutionalize its inventions. This same freedom is what inspired local cultures to connect with the universal aspiration for modernity. Jean-Louis Cohen’s article analyses the tension arising therefrom and the rich seam of interferences that fed into the architectural and publishing scene.

No other theme seems more characteristic of modernist architecture than spatial continuity from interior to exterior. Yet a closer study reveals that the trend was interpreted quite differently in Europe and the States. Gwénaël Clément explores the virtues of staging the Californian horizon in an “art of the gaze” which post-war housing designs experimented with in particular. His article also sheds light on the eminently modernist and Baudelairean theme of correspondences between architecture and the arts of framing.

Le Corbusier also considered the landscape as a key participant in the design process. He made it a construction in its own right, an abstraction that places less importance on the immediate context than on the distant horizon and course of the stars. The confrontation of proximity and distance through incongruous combinations of scale and random objects in buildings, as if in still life paintings, conceals latent meanings. David Diamond explores such meanings in Le Corbusier’s drawings and on sites such as La Tourette that still have much to reveal about themselves.

The sense of a limit applies not only to space, but also to time. The architectural project as an art of “staying the distance”, the invariant whose signs over the centuries are documented in Olivier Gahinet’s article, has been challenged by the advent of an accelerated pace of change. Gahinet’s solution is to think through the issue of ecology not only with words, but also with deft diagrammatic schemes that seek to solve both the challenges of contemporary urbanscapes and project economies.

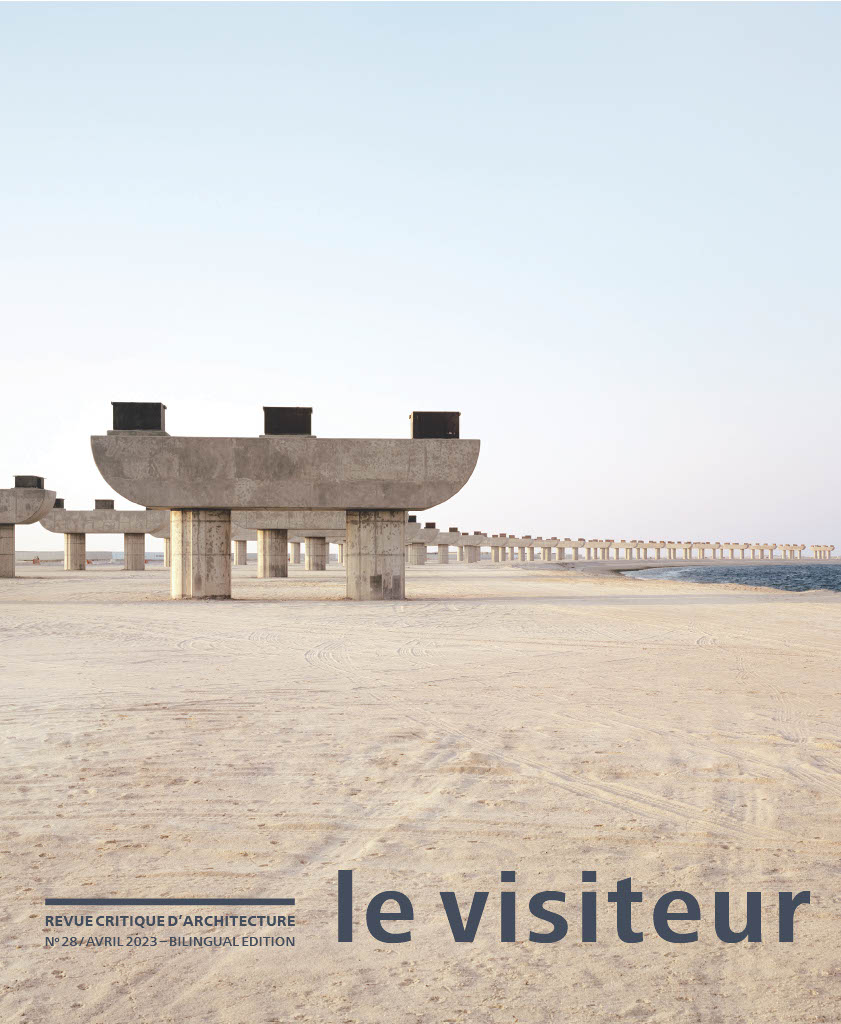

Philippe Potié explores what could be described as the subconscious of modernity, lying in the shadow of technology and calculation. Those twentieth-century designs that enshrine statements of architectural intent affirm the power and eloquence of industrial materials, yet despite positivist claims to progress, they remain attuned to an archaic past dominated by nature and its myths. The archeology of figures and traces that endure in the depths of any given discourse chimes with Pierre Bergounioux’s fine text that seeks to bring a new perspective to European history by focusing on the systems of production that are the source of social order. Bergounioux simply picks out a handful of key moments, such as the invention of the horse collar, to illustrate how history has speeded up over the course of the centuries, concluding with an unflattering assessment of the state of our current civilization.

Whether trace or narrative, the modern is first and foremost a project. To take one example, Auguste Perret’s project for the centre of Le Havre is fully coherent, yet the design’s apparent unity masks a profound dichotomy. On the one hand is the enthusiastic public reception of modernist inventions in the domestic sphere, while on the other, the same public rejects the same principles applied to the urban sphere. Pierre Gencey focuses on the impossible challenge of reconciling two such gazes brought to bear on a single object, something that is symptomatic of the relationship that “the masses” have had with modernity for the past century. Pascal Q. Hofstein’s article is devoted to another highly divisive symbol of modernity: the tower block. He sees it first and foremost as a research zone for studying the urban sphere, defining two categories of tower block historically. His aim is to understand its aesthetic and social aspirations and uncover the stresses generated by the contrasting imperatives of profitability and urban planning. He concludes by outlining a third category, as yet theoretical and still on the drawing board.

Light is a material for architects and film directors alike. The way light changes in various schools of film and in pieces of architecture reflects the way each of the two art forms sees itself. The particular form of modernist light that François Prodromidès describes as “eerie” plays a role in staging the moving body as a captive participant. After all, people living in a given building are the “characters” of its architecture, just as characters in a film “live” on screen. From the Villa Savoye to the sunlit expanses of Stranger by the Lake and the stripped-down modernity of Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle, the article takes an architectural stroll through the history of cinema to illustrate how the two art forms illuminate each other.

Fifty years after his death, Le Corbusier is still sparking heated debates that seem to betray a further, albeit different, anxiety. Antoine Picon sets out to find its unspoken causes, concluding that they lie not in modernity but rather in a phobia of modernity that is symptomatic of a contemporary malaise.

Setting a project within a given cityscape implies de facto, setting it in a given temporal context. With this in mind, the grand modernist gestures are torn in their relationship to the extant setting between the tabula rasa and the need to nod to local culture. They are similarly torn in their conceptualization of how a given project is finished, or deliberately left unfinished as a means of embracing the future. David Leatherbarrow demonstrates how certain modernist projects, far from breaking with tradition, in fact borrow elements from it for new purposes. Modernity posed a challenge to what could be described as art’s address. François Chevrier takes a question that sparked a debate between Stéphane Mallarmé and Leon Tolstoy as the starting point for an exploration of the relationship between the architectural and artistic artwork and its audience, taking dance as his key example.

The theme for this issue explores the capacity to connect past and future; this is also the purpose of a journal that seeks to bring texts alive. Without wallowing in nostalgia, it is tempting to hark back to a golden age when architecture journals were plentiful and sufficiently rich in content to spark major theoretical debates that shaped the history of the discipline, as does Richard Padovan’s “The pavilion and the court”.[1] The current issue includes a French translation of this seminal work to introduce to a new audience, a major study by one of architecture’s great thinkers – and one of a mere handful who seek to spread practical understanding. His article provides a profoundly original approach to the heterogeneous nature of the Modernist movement in its early days.

Each issue of Le Visiteur includes one monographic study. The present issue pays homage to a great architect whose thinking was predominantly transmitted in built projects. Edith Girard participated in all the key political and social movements of her generation. Her built work embodies a veritable panoply of inventions that to date, have not been systematically studied. Her projects unveil their secrets in a lengthy article by two long-standing friends and fellow architects, Patrick Germe and Jean-Patrick Fortin, who each focus on one aspect of her work.

Edith Girard turned social housing into a Gesamtkunstwerk – a way of constructing urban spaces with routes, scales, and its own scholarly typologies, outlining a decent setting for every home. She also made it a way to reconcile opposing aspirations, reinterpreting historical models and opening up territories to embrace the future. In that sense, her work was at the very heart of the modern élan.

[1] In Architectural Review 170, no. 1018, London, December 1981.

Translated from the French by Susan Pickford

The Boom

Pierre Bergounioux

See more+Since it emerged five thousand years ago, literature has been the most accurate expression of successive societies. Through articulate language it offers an approximate version of a certain state of civilization, that is to say the stage reached by the development of productive forces and related modes of production such as slavery, feudalism, market economies, etc.

During the past half-millennium, when Europe has been the protagonist of history, literature has faithfully assumed its fate, each century making its contribution to the saga of Modern Times. The Renaissance, which sought to return to the past, invented the future, while the seventeenth century laid the political foundation of nation-states, the eighteenth century introduced enlightenment, and the nineteenth century heralded revolutions.

The nature of the twentieth century has not yet been conclusively described, or perhaps it is composite and requires several labels. Hobsbawm called it an age of extremes, but it was also one of wolves and, according to Sloterdijk, of explications in every sphere – scientific, psychological, technical, philosophical, political, literary, and so on.

While architects are special people who materially inscribe the spirit of their times in the landscape, their acts are imbued with long-lasting echoes. We all need shelter, need to travel, need to work.

Architecture, like all other spheres of activity, is steeped in the contradiction that drives the historical movement: on one hand, the means and unprecedented perspectives that it draws from the present; on the other, the tyranny of financial capital, the tenacious injustice plaguing our societies, the glaring absence of any political vision following the collapse of actual socialism.

It is these themes – some of them historical yet persistent because crystallized in stone, brick and steel, others entirely contemporary and therefore still indeterminate – that I shall develop.

The Orphaned Word

Karim Basbous

See more+Modernity progressively took wing in the void left by the disappearance of God. In architecture, the long reign of the classical Orders – the yardstick by which the difference of styles was measured – came to an end in the clamor of the Industrial Revolution and the effervescence of the avant-gardes. The break represents far more than a new set of doctrines, ideas, and figures: it reveals a deeper reversal in the fundamental relationship between subject and the knowledge that underpins it in the process of design. This reversal means that the subject is no longer satisfied merely to follow the prevailing framework within which all architectural projects take shape and take on meaning: rather, he steps outside of the frame to explore his imagination elsewhere, even at the risk of endangering thought itself. Hence the hero becomes a father figure.

I focus on some of the torch-bearers who stand throughout the History of the project since the Renaissance to observe modernity in its own right, distinct from the situational modalities in which it has been manifest, which have tended to reduce it to an architectural style or an ideology. My aim is to shed light on its ontological definition. What does it mean to be modern? Beyond the flood of ordinary projects that reinforce the established grammar, what stance is the starting point for a new language, forged in the studio of the self by an unprecedented reciprocal arrangement, destined for universality, between forms of knowledge, technology, and nature?

“To Anyone!” or, The Adventures of Spatial Difference

Jean-François Chevrier

See more+In 1898 Mallarmé offered this quip in response to criticism in Leon Tolstoy’s recently published What is Art? The question of art was being raised in two metropolises at the two ends of Europe, and the question was whom artists addressed. Tolstoy’s answer was “the people,” everyone, without exclusion. He therefore criticized the “obscurity” of the poetry of Mallarmé, who replied that artists did not address everyone but anyone, namely a socially and ideologically indeterminate audience, composed nevertheless of individuals who were favorably disposed and sufficiently interested.

The debate between the two writers – a devout novelist and an atheist poetic – is dated but still sheds light on the current situation. Raising the question of art in terms of address involves a definition of the modern audience as well as the definition of any constituted community in the public sphere. It also entails spatial differences, and thus even architecture and urban politics.

International, Binational, or Transnational? Modern Architecture without Borders

Jean-Louis Cohen

See more+National borders, fluid anyway in 20th century Europe, have proved porous to the ideals and forms of “modern” architecture. Numerous “radical” architects – to the extent that this epithet has meaning – claimed membership in an international movement, and paid dearly for it during reactionary phases in Russia, Germany and Spain.

At the same time there has been no shortage of attempts to use stylistic elements responding to the constituent elements of new national identities, from Finland to Czechoslovakia to Brazil. Yet it would be misleading to restrict oneself to the dialectic between international bodies such as the international modern architecture congresses and their avatars, the international conferences founded by Pierre Vago; or between diverse networks of urban renewal, on one side, and intra-national groups and professionals on the other.

The interferences between national cultures and bilateral relationships, informed by complex and sometimes time-worn representations thereof, have been no less intense: think of the role played by the journal L’Art Sacré in post-1945 religious architecture. By observing some of these interferences through the projects that crystalized them we will be able to view more clearly the discrete images that modernism borrowed for itself between its foundational period and its terminal crisis.

Possible Realities and Real Possibilities: Architecture in the Modern Age

David Leatherbarrow

See more+The ideas of modernity and of project making that were developed in early 20th century architecture reinforced one another. Proponents of the new architecture had no doubt that the new century was a time of profound historical change. They were also confident about the role to be played by their designs: the landscape of modern life would result from the work of imaginations attuned to conditions that had dramatically changed – emancipated from the lived world though their visions may have been. Yet, as the years and decades of the modern period unfolded adhesions to pre-existing conditions, even traditions, came to be seen as inevitable when actual sites, programs and builders were used as the materials of project realization. This paper will address a single question: What is the relationship between the “possible realities” imagined in early modern projects and the “real possibilities” of building the modern world?

Onyx and Steel: the Archaic Duality of Modernism

Philippe Potié

See more+Although the heroic narrative of modernism – of which Giedion was one of the most passionate propagandists—had the merit of galvanizing an avant-garde movement, it also paved the way for an inverse approach to the future in which disappointment replaced earlier hopes. Nowadays, the mourning for that ardent modernism has ended, and we can take stock more serenely, revealing deeper structures of thought. One of the structures discussed here – less doctrinal, but more rich and complex – seems to have been built not on a defensive, univocal narrative but on the antithetical dualism embodied in the nature/culture dichotomy (whose generative power in the construction of myth was revealed by Lévi-Strauss). Given this perspective, the article shows how modernism’s most famous works staged “the rise of machines” against the backdrop of an elegiac chant glorifying the primitive forces of nature. Going further, it is suggested that modernism be interpreted as a constantly renewed attempt to depict an archaic dualism that pits Promethean technology against the subterranean powers of Gaia, or mother earth. Ranging across the history of modernism from the Barcelona Pavilion to late works by Wright, the article sketches a line in which the emergence of Ronchamp assumes its full meaning. This will lead to a grasp of the profound connection that links, from an unsettling angle, the inexorably accelerating technological time-frame to the immutable pace of the life cycle of primordial earth. Along the way, the article shows how this modernism bore within itself the seeds of postmodern deconstruction, which appears as a natural offshoot.

Domestic Paradise in an Urban Hell

Pierre Gencey

See more+The modernist movement drew on utopian narratives to reinvent the city, the street, the home, the kitchen and even the chair. It succeeded in part, since in most homes the idea of comfort still expresses itself through hygiene and other rationalist principles, backed by equipment that is both standardized and innovative. This phenomenon can be traced to World War II when, with so much at stake in terms of reconstruction and growth, the media were particularly interested in housing issues. And yet, in the field of urban planning, a violent reaction occurs against the this apparently successful mixing of modernism and home design: the rational and hygienic city, standardized and technologized, tends to evoke the hellish images of dystopic novels rather than the ideal of progress. Why this divergence, this antagonism?

The attention currently being paid to Le Havre’s reconstruction and to its model apartment, the work of Atelier Auguste Perret and of interior decorator René Gabriel, offers clues: Interior decoration affords each individual, within the bounds of domesticity, the illusion of choice and the feeling of progress in that person’s personal life, as if the collectivity were working for and sought to liberate him, or her; within the urban environment, modernist construction demands an esthetic submission. From that point on, everything is turned upside down…

The Unsettling Light

François Prodromidès

See more+In 1930, Pierre Chenal shot a silent film in Le Corbusier’s recently completed Villa Savoye, titled L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui (Today’s Architecture). Just before a shot of the dining room, an intertitle stated that, “This scene was shot without the use of artificial lighting.” Architecture thereby converged with movie-making in the context of a declaration of modernism where light played an essential role: interiors could henceforth be filmed bare, without floodlights. In the photogenic breakthrough of the day, architectural space itself compensated for the slowness of film stocks. In 2014 I found myself shooting a film in the same villa. Visiting it for the first time, the ubiquity of light struck me as, if not blinding, rather unsettling – where could the eye dwell in this all-lit machine for living? Parading my eye through the house, I recalled several film-makers who had been concerned with the issues of framing, light, and modernist spaces. I recalled that natural lighting had also been one conquest of cinematic modernism, and I wondered about the role it was expected to play in the Savoye family’s little bourgeois theater.

Borrowing Landscape and the Enigma of Corbu

David Diamond

See more+This essay examines the primacy of landscape in the work of Le Corbusier – landscape in its actual and symbolic representations, landscape as a source for topographic isomorphism in his formal vocabulary, and landscape as a metaphor for the natural order of things.

For Le Corbusier, the techniques of borrowed landscape become a means to negotiate dialogue between his architectural works and the sites in which they would be constructed. Using borrowed landscape as a three-dimensional analogue for what photographers and graphic artists do when they crop and compose images into new networks of associations, Corbu achieved a means to dismantle common protocols of visual communication. He collapsed time and distance with irrational juxtapositions, offering illusions in place of certainty, and riddles in the space where the prosaic facts of his architectural works meet the extended contexts within which they are built.

Without excessive deference to a project’s immediate surroundings, Le Corbusier brought his projects into dialogue with distant, external coordinates: sometimes urban, often topographic, and increasingly, towards the end of his career, the cycles of diurnal and calendrical time. And with these new relationships deployed, he embarked on secret communication with an audience whose alertness, attention and patience conferred on them eyes allowing them to see. This research examines how Le Corbusier conceived his works to be related to the landscapes in which they were built, and explores this aspect of the poetic vision that underpins his work.

The American Horizon

Gwenaël Clément

See more+20th Century Fox employs CinemaScope for the first time in 1953. It’s a technique that compresses the image while shooting, to expand it later during projection. American cinema takes advantage of this invention to get out into the open, leaving the studio to return vast natural landscapes to the new, panoramic screens. From then on this broadening of the camera’s field and associated tracking shots will turn natural space into entertainment for darkened movie-houses.

In 1960 two architects will each deliver a house broadly planted on sites in the Los Angeles hills which previously had been deemed unbuildable due to their steep grade. These projects are emblematic of a new relationship to landscape. John Lautner, in his Chemosphere, and Pierre Koenig in the Stahl House, design spaces that escape the foreground to take advantage of a seemingly limitless view. To the contemporary principle of visual and functional continuity between interior and immediate exterior – part of the biniomial tradition of house and garden espoused by modern theorists – Koenig and Lautner substitute the idea of an “ungrounded perimeter” widely and exclusively focused on the faraway. At this point the idea of a face-to-face rapport with a wider landscape seems to replace that of a spatial continuum as a paradigm of modernity. To that end the horizon tends to approach, invite itself into the house, to the point where it takes over the house’s space and imposes its own directorial view. It’s in this new relationship with the outside, which echoes Cinemascope, that our way of being in the world is transformed. It’s this other modernity, offering another, parallel way for architecture, and whose ultimate effects remain to be seen, that is the subject of this text.

Defying the World

Pascal Q. Hofstein

See more+The tower, an iconic building of the quest for verticality, has either been perceived as a technological achievement or as singular signal on the horizon line.

From the Pittsburgh Cathedral of Learning to the late contemporary towers and the John Portman’s gigantic hotel lobbies, two specific types will be examined: The first type aims at being efficient while stacking horizontal layers. The second one hollows out a part of the tower in order to fill its remains with a monumental and vertical hall space.

We shall endeavour to develop a third type, which ambitions height as a means of developing “the vertical,” thus transforming usual references: the ground warps up, invites typical and traditional programs to inhabit the height and its apex. The sky is distorted, bent and perceived as a picture plane.

Going the Distance

Olivier Gahinet

See more+Since the beginning of modernity (which like Panofsky, we will date to “when Goethe died”), two apparently contradictory tendencies have coexisted within architecture: the first sees the project as a way of transforming the world; the second aims for permanence. On one side, the will to transform; on the other, the desire to last. When a synthesis is made between the two, it will result in places that are out of time, seeming to be available forever and capable of housing the nostalgias of the future. This modernity was constructed in relation to the industrial revolution. Today, a new revolution is needed: one that would accompany the necessary “loosening” of man’s grip on Earth (the fight against climate change being one aspect of this); one that would leave our fellow occupants of this planet their own space; one that would restore man’s dignity and self-sovereignty.

The question will be, what “architecture of parsimony” could accompany this future revolution, and what spaces could, in turn, be the places of future memories, so as to continue the modern adventure by inhabiting – at last – time.

Help! Le Corbusier is Back, or, The Difficulty of Being Postmodern

Antoine Picon

See more+The fiftieth anniversary of Le Corbusier’s death has been marked by numerous events celebrating the imposing oeuvre forged by the architect, urban planner, draftsman, and painter. Yet the anniversary has also been characterized by a polemic over Le Corbusier’s fascistic and anti-Semitic tendencies in the 1930s and his behavior during the Vichy regime. Without going into the details of that polemic, this article discusses the deeper reasons that triggered it, beginning with a fairly widespread rejection of modernist architecture and town planning even as modernism ceased to reign over urban centers and ghettoized suburbs. In a certain paradox, this rejection of modernism may well mask an even more fundamental angst over a postmodern condition that some people feel is more threatening than the heroic modernism embodied by the figure Le Corbusier.

The Pavilion and the Court

Cultural and spatial Problems of De Stijl Architecture

Richard Padovan

See more+Le Corbusier and Theo van Doesburg first met at an exhibition of De Stijl architecture curated by the latter at the Parisian gallery L’effort moderne. Their meeting represented the clash of two opposing principles of modern architecture.

The first embraced the ideal of a pavilion as an isolated structure in natural space, as traced back to Laugier’s and Rousseau’s essays of 1753, through the nineteenth-century romantic suburban villa to Wright’s prairie houses. This principle contrasts with the ideal of a court, incarnated by walled dwellings and urban squares in densely populated cities.

The clash between these conflicting principles was quelled in 1929 by the Barcelona Pavilion and Villa Savoy: the former was essentially a pavilion within a court, while the latter was a court within a pavilion. However, the resulting truce was only temporary. This article explores the reason for that failure, which resides in unresolved conflicts with society itself, namely between the needs of the community and the needs of the individual, between equality and freedom.

“Framing the Landscape”

Patrick Germe

See more+Edith Girard was a member of the “critical generation” that emerged from the ruins of the École des Beaux-Arts in the late 1970s. How did she manage to pursue a mode of architecture that existed outside prevailing dogma? How did she develop a style of teaching and working that opened onto a “new reality”? This article explores some key aspects of this modern urban architecture: place exposed to alterity, the representation of the exterior on the interior, privacy on a collective scale, and the courtyard as the key space of a housing block with open volumes.

Edith Girard’s Strada Novissima

Jean-Patrick Fortin

See more+With her first work, Rue Carnot in Stains, 1983, Edith Girard (1949–2014) became a leading figure in the critique of the dominant postmodernism. How did she make a modest suburban street into a Strada Novissima? The Stains project takes on board every dimension of the city: the continuity of historical time and continuity of space (here, a suburb), the science of line and layout, depth of perspective, the role of collective housing, the ground-level experience and walking, the organization of programs, and the territory. Whereas the grands ensembles created a limp presence, lacking in tension and orientation, Girard’s Strada Novissima offers a presence that, in its scale and proportions, is enveloping. Here, the city signifies; it speaks to the citizen’s emotions. All of which left critics and institutions speechless.