Description

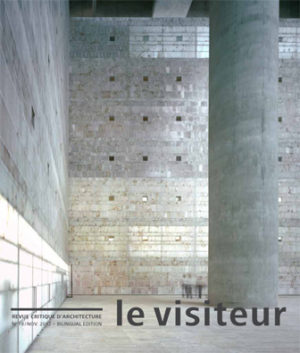

Publication date: 2025

Editorial : Interiors

Karim Basbous

Read moreThis thirtieth issue of Le Visiteur examines what every treatise addresses, what no doctrine can escape: creating a space removed from the rigours of sky and earth, from intruders and beasts—a space that is defined, qualified, and meaningful. The artefact of built space organizes our lives and actions, establishes thresholds, divides what needs dividing the better to cohabit with others and represent a concept of society. To do so, it draws on construction, decoration and furniture, alongside notions such as suitability, comfort and hospitality and conceptual tools like the free plans and fluid spaces embraced by twentieth century architects. The density of the fabric, sources of light in rooms, scale of buildings and framing of the exterior also define the quality of the spaces we inhabit. Yet from the roofs of our houses to the vault of the sky, the notion of interiority proves relative, giving us a key to read and define the conditions of our physical and institutional existence.

From the concept of environment to that of habitat, from immersive theories to the newfound importance of the verb “to get some fresh air” since the last health crisis, the relationship between the body and its surroundings has, in every era, engaged political thought, technical choices, and an order of things to which the architectural project contributes. The ambition of this issue is to nurture critical thought regarding societal choices: at a time when some are calling for a brand new economic model to try and reconcile social justice and the very survival of our ecosystem, the concept of the interior needs updating, if only to challenge the isolation of single houses and the cramped space of apartment housing and rethink the height of buildings, the shape we give public space, and the way we arrange housing from the street and design open interiors. This is what Catherine Furet sets out to achieve, placing the project for collective housing back in the context of overarching urban history. Her urban culture and talent for architecture let her bring her own fresh take to the qualities of the historical urban fabric with the tools of contemporary production. From project to project, she makes the case for urban space as a succession of nested interiors extending from the sitting room to the street. Readers will find in this issue a follow-up to The European Dream in our previous issue, inasmuch as there is such a thing as a notion of the interior—both urban and domestic—unique to Europe. It connects the principle of protection to that of openness, illustrating our need to both share busy spaces and withdraw to a silent bedroom.

The first interior that comes to mind is inevitably our own home. Only writers and architects can make an everyday interior the object of thought that lingers, contemplates, dwells. For some years now, Thomas Clerc has been expanding the spaces he lives in to make them a world in their own right, from a three-room apartment to an entire Paris arrondissement. A revelation made during the lockdown inspires here a critical reflection on the dissolution of the boundaries of private life, a concept that took shape starting in the eighteenth century. “Connected objects” contribute to this process of dissolution; viewed from another angle, they are the distant descendants of the ghosts that fed the imaginations of storytellers and film directors. Antoine Picon points out that our homes have never been devoid of invisible presences.

The notion of interior is necessarily connected to its counterpart: Pascal Hofstein’s article exhausts the opposition between interior and exterior, to the point of generating a third space. What he calls the “space of conflict” sheds new light on the major projects of the last century, particularly Le Corbusier’s Mill Owners’ Association Building in Ahmedabad, whose ambiguous spaces are given a name here. My own article takes the angle of movement to explore interiors through theatre, “traversing the plan” in both historical and spatial terms, to grasp not only the thinking behind the layout of its lines, but also the complex relationship between the order of the plan and the design of the façade, against which the urban interior rests.

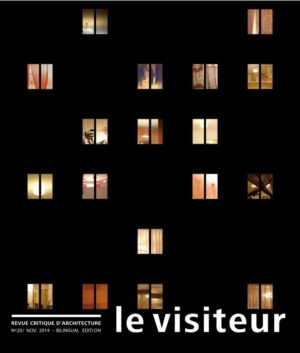

Marion Picq’s passion for urban windows leads her, through an interplay between painting and architecture—two arts that have so often imitated one another—to explore the stakes of this threshold, which belongs as much to the intimacy of our apartments as to the shared space of the courtyard or the street. Emanuele Quinz shifts perspective, studying interiors based on objects rather than walls, opening up an entire new history other than the history of architecture; what has come over time to be known as design turns out to be a contested field.

François Frédéric Muller explores what time does to built interiors, dwelling on the capacity of buildings to last, what for, how, and at what cost. There is no architectural space without a light that defines it; the northern light, which Jean-François Marti has patiently observed—where interiors take on the color of the sky and the light of dawn—offers insight into the work of Alvar Aalto and, more broadly, the clarity without which no spatial depth is possible. The issue closes with a piece by Annalisa Viati Navone on one of the most open interiors of all: the Saracena, a house designed by Luigi Moretti in Santa Marinella. This masterpiece, which deserves to stand alongside icons like Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Wright’s Fallingwater, showcases the talent of the most baroque of all the Modernists.

Translated from the French by Susan Pickford

Locking In and Down

Thomas Clerc

Read moreIn 2007, before writing Interior in 2013, I published a description of the 10th arrondissement in Paris, where I had an apartment from 2001 to 2017—the exterior thus contained the interior. Then I moved, and began to write a second part of Paris, musée du XXIe siècle, this time devoted to the 18th arrondissement, where I had set up my new home. In between times, the stakes had been altered by the lockdown imposed on the world’s population (2020–2021), inevitably changing everyone’s view of living at home. I drew several conclusions, which I would like discuss here: first, the obviously porous nature between interior and exterior (which I had already illustrated in Interior) limits the autonomy of both spheres, public and private; second, there is a fundamental difference between confinement deliberately chosen by an individual and the political lockdown imposed by bio- and techno-powers; and finally, we need to rethink domestic inequality, since space is not the same for all. Two adversaries thereby emerged: the proponents of remote working, which abolishes the notion of personal space by merging computer with home; and the advocates of cabins, propelled—behind their virtuous discourse—by a problematic rejection of social issues.

Volte-faces

Pascal Hofstein

Read moreIn Hebrew, panim means “before” or “face” as well as “within” or “interiority.” This linguistic ambiguity can also be found in architectural projects. It is all a matter of delineating inner limits, installing the conditions of intimacy and conceiving the relationship with light and the horizon. Starting with the drawings of Lebbeus Woods and several utopian projects in Manhattan, and looking at building by major figures of modern and contemporary architecture, we will see how interior palace is shaped by a series constant about-faces, from inside to outside and back.

Assembling Internal Spaces

Catherine Furet

Read moreThe notion of ‘interior’ lies at the very heart of spatial design. The relationship between an ‘inside’ and an ‘outside’ goes far beyond the simple delimitation between the two, however richly that may be expressed, entailing a plurality of scales and perceptions. When we are ‘inside,’ we remain where we are: the walls around us ensure our privacy, but we are not immobile. This interiority only exists in reference to an exterior that we’ve just passed through to reach our home. Surely making an ‘outside’ feel like another ‘inside’ is an aspect of designing a living space? How can we design welcoming, familiar environments sheltered from the turmoil of the city? What is the best way to conceive internal walls with discreet openings that encourage us to slip through them, or install unexpected vistas of open spaces that provide a source of light? How we organize and assemble housing units allows a multitude of discoveries to be made, in particular with regard to the sense of ‘indoorness’ with which we invest open-air spaces between surrounding volumes, thereby augmenting our living space. The design of a set of housing units requires interaction with what lies outside them; the project is rooted in whatever has preceded it and whatever looks onto it: surrounding buildings, the layout of the site, walls, trees, the slope of the ground, all these have a contribution to make and help to stimulate the architect’s imagination. It is in this dialogue that an elsewhere gets created, one that opens up near and distant horizons drawn by the skyline, allowing us to dream and perhaps even to be in the world.

What moves us

Karim Basbous

Read moreWestern architecture began as exteriority, with the Hellenic pedimented colonnade adorning the skies, while the interior was a dark, blind, lifeless space. Over the following centuries and during the Roman empire, the aim became to conquer the interior, bringing light—both literally and figuratively—into the space between the walls. Crossing through the outer walls brought us into the civilisation of interiors that still defines us, though outer walls still retain their prestige. What drove Greek and Roman builders was not a historical object but a display of intelligence which let architecture put down lasting roots as a principle of harmonious arrangement in both political and aesthetic terms. This offers insights into the etiology of the contemporary malaise, since architectural figures have lost their weighty significance. The line of descent that can be traced from Antiquity to the present day sheds light on what makes the grandeur of a plan and a façade, whatever their style and technique. I draw on a range of examples to study the unique spirit of each geometrical view and their singular harmony and pin down the signs of a thought that assigns the most noble aim to the architectural project: making practical and symbolic programmes the launchpad for a sovereign art whose purpose is to make our own lives and acts more beautiful.

Vis-à-vis

Marion Picq

Read moreKafka says of the street window that it will catch the attention of even the most jaded man, “so that finally he’ll dive back into the human harmony.” As for Bachelard, he describes the street-facing window as an opening that allows the streets, “pipes that suck people away,” to swallow us all. At this threshold to the interior an encounter happens that might be the most delicate architects ever have to set up: the face-to-face meeting between home and city. The urban window can be a place of conflict as much as it can be the agent of its dissolution. An architect’s practice is nourished by a culture that associates the window with a way of “inhabiting it”; but multi-family housing makes the window vulnerable to a slew of demands—management of proximity and avoidance of promiscuity are piled on top of the usual requirements of lighting, ventilation, a hierarchy of views. Here we will seek to better understand this powerful mediator which has inspired so many representations; to see how one’s design might create—bearing in mind the stakes implicit in multi-family dwellings—a certain habitability.

The Invisible Wall

François Frédéric Muller

Read moreThe ruin, whether archaeological or created by war, is a building that has lost its capacity to accommodate a use—or, as we now say, a program. But rather than this utilitarian vision, I propose to look at how a ruin is rather the loss or erasure of the limit, or even better, the blurring of the limit. As anyone who has visited Pompeii, Delos or a theater of war can appreciate, their stone landscapes are made up of patchy walls and roofs that no longer completely define what is internal. These fragmented boundaries are unsettling; they make us understand, through absence, how a boundary is reassuring, to what extent it allows us to distinguish between people, to extricate ourselves from the dangers of the world. But in the end, these ruins are just an obvious, all too easily understood version of what it means to lose boundaries. Art historians, poets and reporters have explored all their representations. What is more interesting is to measure the extent to which the strangeness of the ruin as a loss of limits has inspired contemporary literature, and how part of our built environment has drawn on this imaginary of erasure, for better or for worse, to the point that architecture sometimes completely disappears.

Haunted Houses: From Ghosts to Artifical Intelligence

Antoine Picon

Read moreInhabiting a place means recognizing that a dwelling is much more than an accumulation of materials comprising floors, walls, and ceilings; it means accepting that the place is, in a way, haunted. Contrary to what we often think, being haunted is related to an absence that the ghost fills in a very incomplete way. Underneath that absence lies an elsewhere or otherness that imparts full meaning to the occupation of a house. “Here” feeds on “elsewhere,” the “present” feeds on the “past” (or what will happen next), and “life” feeds on beings who are different yet dangerously similar. Some haunted houses reject their new occupants. Such cases are sufficiently rare to make the headlines. Their pathology also says something about what it means to inhabit a place. This paper discusses notions of interiority and being inhabited, beginning with old-fashioned ghosts and ending with contemporary specters of artificial intelligence in the home.

The Life on Interiors

Emanuele Quinz

Read moreThe history of design has accustomed us to sequences of remarkable works, men and women of genius, major theoretical turning points and radical social transformations. The genealogy of modern design—glorified by our museums—is a portrait gallery in which the history of design acquires the legitimacy of a disciplinary field, becoming a “domain.” I would like to break away from this approach and plot another history of design, starting with interiors. The most essential, the most intimate, the “first place” of life is the personal room. Drawing on historical and contemporary examples, and bringing together critical theory and literature, I propose to use personal interiors as a way of talking about what design is, what we do with design, but also what design does to us.

Atmospheric Figures in the Northern Light

Jean-François Marti

Read moreIn Towards a New Architecture, Le Corbusier cites Athen’s Acropolis, Hadrian’s Villa and the ruins of Pompeii in his argument that “the outside is always an inside.” Alvar Aalto’s travel sketches illustrate a similar fondness for ancient Greece and Italy. However, the low trajectory of the sun in Finland offered him a resource that he successfully exploited, and which would—as in the work of other Scandinavian architects—become a distinguishing feature: horizontal light. Here I discuss the singularity of these architects’ interiors through the prism of Nordic light, by means of which they have reversed Corbusier’s aphorism so that it becomes “the inside always appears to be an outside.”

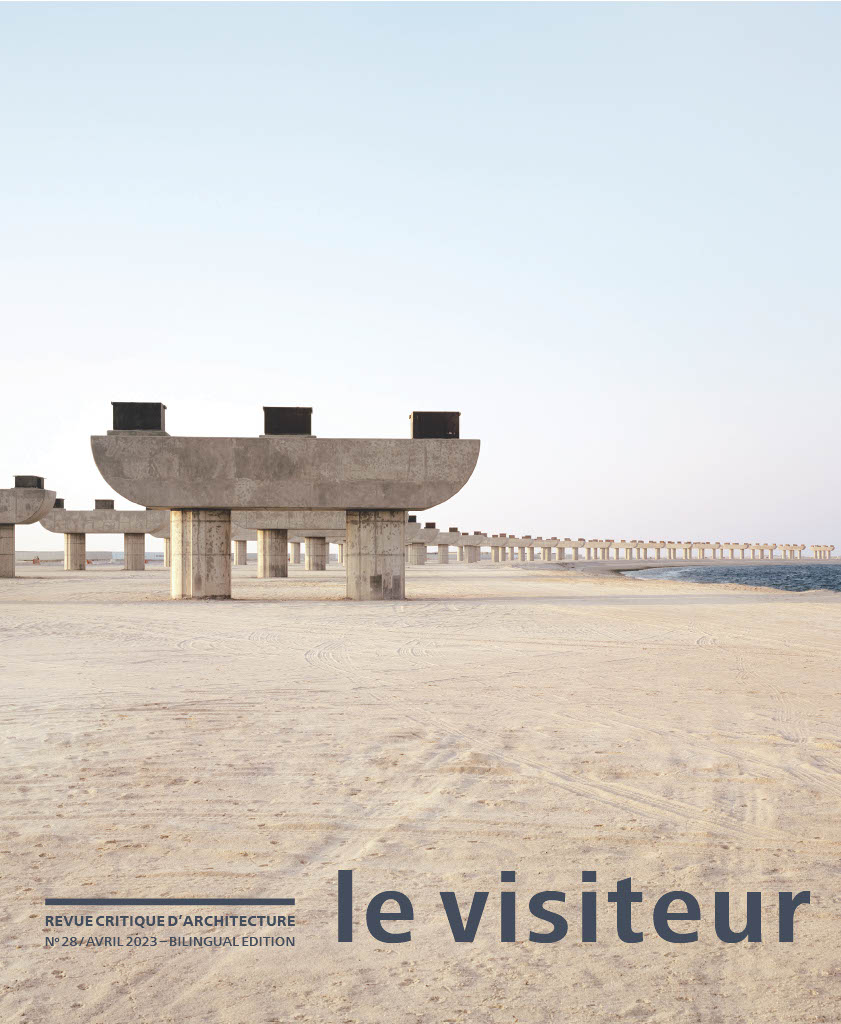

Objectivized Self-Awareness: Experiencing Luigi Moretti’s La Saracena

Annalisa Viati Navone

Read more“Especially in cases where it is the principal reason…for the existence of [a building], internal space can be defined as the richest seed, mirror, or symbol of the entire architecture unity,” wrote Luigi Moretti in 1954. Moretti was the first person in Italy to precisely define the features of interior space, which he deduced from his observation of Baroque and modern architecture. Making project consistent with philosophy, Moretti devised interior spaces as processional zones, light-spaces that breathe and vibrate, endowed with what he called “energetic charge.” His work thereby converged with the thrust of Op Art artists like Vasarely, of cyber artists like Nicolas Schöffer, and of “artists of another kind” (art autre). He described this art as “meta-historical baroque.” This paper takes a look at interior spaces created by Moretti notably at Villa La Saracena, completed in 1958. The sequences of space unfold from the outside, traversing volumes that expand and condense, via an artistry of thresholds, transitions, and surprises that punctuate the experience living in it. That experience is examined here through the prism of objectivized self-awareness that Robert Vischer called Einfühlung.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.