Description

Publication date: 2022

Editorial :

Karim Basbous

Read moreEver since the polis became a foundational concept of Western society, the political order and urban order have gone hand in hand, the former bound up with institutions and their prestige, the latter with sites that represent and host the community. Today, the crisis in representative democracy often prompts us to appeal to the city as polis, as if harking back to the origins of our civilisations were a requirement for neutralising their failings. What of the polis in the age of internet, globalisation, the increasing privatisation of public services, decentralised finance and digital surveillance? What model of citizenship have we unwittingly followed the path to when we let new habits creep in, when technology lets us order shopping in seconds and delivery in record times – at the cost of a far-reaching challenge to social, ecological, and economic harmony? What vision for society can unite people living in overcrowded megacities, or whose sole horizon is an identikit housing estate and the local shopping mall? What vision of the future lies behind the expansion of working from home and remote meetings? Is the polis, born of public debate in the agora, still tied to the idea of a site representing democracy and dialogue, sparking its vitality? A few months prior to the covid crisis, French roundabouts had become soapboxes for calls for new social bonds; no answer has been forthcoming. Yet can it not be argued that public spaces for public speaking are exactly what are missing from most urban planning visions from the twentieth century on, whether they look to the future or the past? Visions by modernist designers such as Broadacre City and the Plan Voisin and attempts at post-modernism such as Euralille, movements harking back to the past such as New Urbanism, and more recently, the untrammelled liberalism of new developments straight out of the pages of a catalogue, all have something in common: they are lacking whatever it is that makes locals into citizens. What political and social reality is this lack symptomatic of?

Such questions underpin this issue of Le Visiteur, which opens with a legal perspective shedding light on institutional shakeups. The space of speech is at the heart of Alain Supiot’s article, which draws in the status of individuals, the role of symbolic systems, and the place of politics and economic powers into one sweeping overview extending from the Greek agora to social networks. The law is not enough to prevent the violence that infiltrates societies, but law is the starting point for standing guard and, as people have always done, subjecting the order of the world to critical thought. Étienne Barilier also offers a unique slant on combining political construction and building in stone through the fine example of Thomas Jefferson’s design for the University of Virginia campus. Barilier has written a meditation on the —now somewhat forgotten—notion of ideality, long foregrounded in paintings and architecture, with depictions that made their mark on the history of art. Two philosophers then explore the twenty-first century polis. Nadia Tazi begins with an analysis of a city without polis, shedding light on the dismantling of an understanding of time by which countries in the global north and south live differently in a splintered present. Pierre Caye takes stock of the rarefaction and weakening of sites in the course of a process of globalisation that has transformed contemporary cities and their status; he demonstrates how their durability cannot be solely rooted in artificial intelligence and smart cities but must—now and always—be about projects.

Two emblematic cases of the journeys of Middle Eastern cities round off the articles. Stefano Corbo takes us to Beirut, where the political and urban landscape come together in a building whose fate is as unique as its design—an old cinema built in an ovoid shape, standing in the city centre. The article describes what the “found object” in the heart of Beirut has come to symbolise. The Louvre Abu Dhabi reifies an often overlooked social and political reality, brought to the fore by Alexandre Kazerouni behind the façade of speeches and projects. Corbo and Kazerouni shift the viewpoint to geography and culture, while Laure Ribeiro turns to the heart of our societies, turning the spotlight on a social group rarely represented in the polis—children. Their gradual restriction to specific spaces over recent decades has played into a segmented public space, reflecting a society prepared to sacrifice the freedom of its youngest members to alleviate the responsibilities of their elders, progressively abandoning the shared space of spontaneous cohabitation familiar to older generations. Over the centuries, the polis has become disconnected from urban space, dissolving and disaggregating to make way for a territory with fuzzy boundaries and unprecedented shapes and qualities. Nathalie Roseau draws the map of this reality and compiles an inventory of the concepts and notions that emerged to define it; she then explores the distance in urban planning between what people do and what they say.

This issue’s Varia section offers a new translation of a text by Yve-Alain Bois untangling the aesthetic issues raised by Cubism to decide once and for all what belongs to painting and what belongs to architecture. The issue closes with a brief text on grand themes, as Franco Purini explains what inspired two series of drawings, speculating on architectural space: in just a few lines, he revives our taste for theory.

Translated from the French by Susan Pickford

Giving Credit to Words

Alain Supiot

Read more“Oxen are bound by their horns, men by their words.” This old legal adage applies to a cité (city-state) which, unlike a ville (city), does not refer to a population assembled on a specific territory, but rather to an association or commonwealth of citizens under the aegis of a shared law. This citizenship can be exercised at various levels, from the village to the whole world, yet always rests on various types of “assemblies of speech” that enable citizens to agree on a fair representation of what is and what should be. But in order for such speech to bind the commonwealth together, it must be creditable. Today, however, many signs point to a loss of faith in speech, whether it be political, commercial, or scientific. In an effort to grasp the underlying causes of this discredit and the violence it engenders, this article discusses the institutional conditions that favor an exchange of words rather than blows, then goes on to propose ways to restore credit to speech in the commonwealth of the twenty-first century.

The Machine of Machines

Pierre caye

Read moreThe city is the big story of our time. Since 2008, more than half of the world’s population have lived in a city, and by 2030 the figure will probably be close to 60%. The demographic attraction of the city is boosted by its economic dynamism. It has become the centre of production and innovation, the heart of the productive system and its economic organization. Initially, the contemporary city appears like a technical mega-system, the system of systems, the infrastructure that brings together superstructures and other infrastructures, or better yet the machine of machines that interconnects the different networks that structure urban life. But the machine of machines is not a means of production like any other, of the same nature as the machines it coordinates. The city gives another meaning to the notion of machine, which is why it is called on to play a fundamental role in productive transformation, at least from the moment when the specificity of its design and intelligence is taken into account.

Time Trouble

Nadia Tazi

Read moreIt is unusual for City and town to coincide in a people’s image of itself: the first aligns idealities that, while expressing a history and an identity, raise up the universal and therefore the timeless as an end in itself. The second mixes different time frames in its singular historical layering. Dyschronia is neither the acceleration produced by modernity, nor the simultaneity of several historical orders within a given space; rather, it joins together opposing representations of the world and figures a “constellation saturated with tensions” (Walter Benjamin). Many countries in the Global South have known and are still experiencing these ruptures in self-presence induced by modernity, a regime of historicity that is other and is not metabolized in politics because it has too often been imposed in an authoritarian manner from outside and above. In these cracks monsters can insinuate themselves. What is happening in the North now, now that the dyschronia is such that the “tiger’s leap into the past” in order to seek a model there is becoming impractical? Are the City and its political vision becoming absent and is algorithmic computation completing the disenchantment of the world, cementing the society of control and the reification of social relations? We can envisage such a rending in a community’s consciousness of itself when the relation to time is confronted with a mutation as deep as the one announced by the dissemination of artificial intelligence, an upheaval whose premises can barely be perceived, and whose radicality can be compared to the disruptive power of the Neolithic revolution.

Jefferson’s City

Etienne Barilier

Read moreThe Ideal City: this title refers to the urban landscape painted in the late 15th century on the famous “Urbino panel”. A city as beautiful as a dream but devoid of human beings. Will it cease to be ideal if it is inhabited by men and women? Will its deserted main square never be an agora? More than anyone else, Thomas Jefferson—a fervent admirer of Renaissance architecture, and an architect himself—was aware of the twin meaning, architectural and civic, of the word “city”. Even if he didn’t draw up the plans of an entire city, he drafted those of the University of Virginia, his ideal city, one that was not going to remain uninhabited. Can it be said that, through its architecture, this city embodies the democracy of the Founding Fathers? And, if that is the case, how are we to interpret the pre-eminent contradiction in Jefferson’s thought, given that he always owned slaves? Considered in a broader perspective, does it make any sense to speak of an architecture of democracy, or an urbanism of the free man?

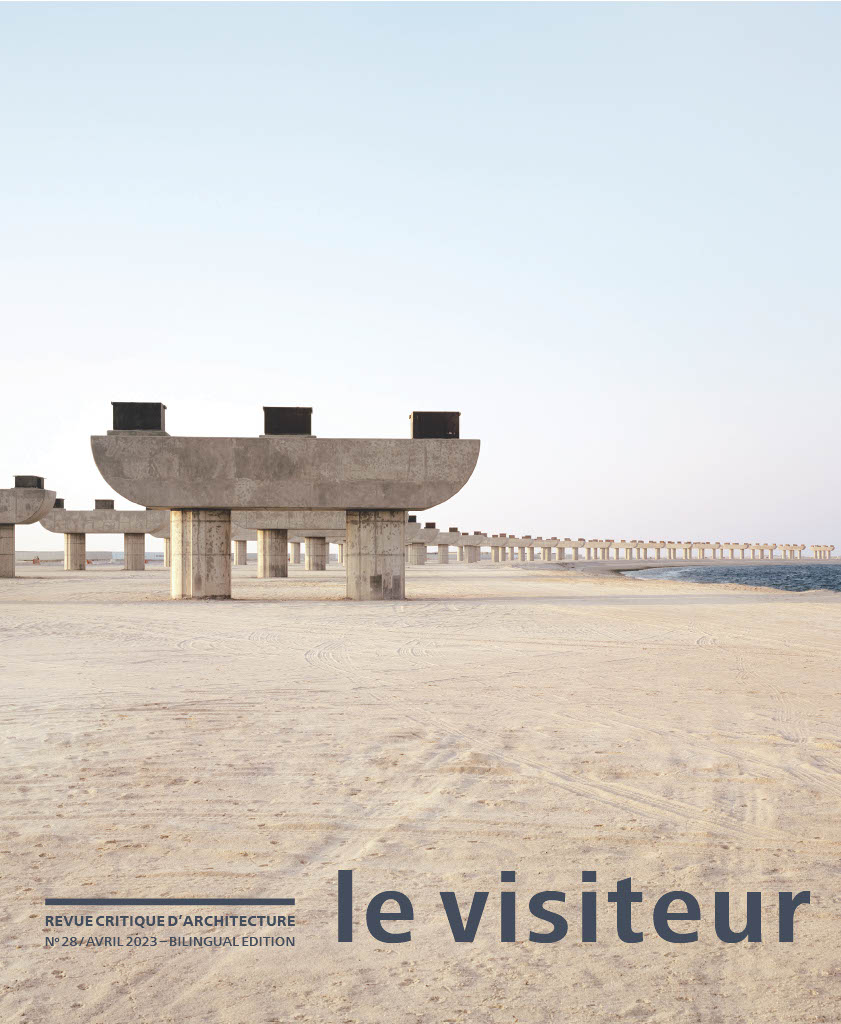

The Scars of the City.

Stefano Corbo

Read moreOver the last 18 months, Lebanon has simultaneously faced an unprecedented series of dramatic situations: the exacerbation of a systemic economic crisis, which has seen the country’s GPD decreasing from close to US$ 55 billion in 2018 to an estimated US$ 33 billion in 2020; the diffusion of COVID-19; and, also, the terrible explosion at the Port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, which has produced hundreds of victims and thousands of injured, with damages estimated around $4 billion, concentrated in housing and cultural heritage. Significant areas of the city’s waterfront, as well as historic buildings, hospitals, infrastructures, warehouses and the major grain silo, have been seriously damaged. Today, in the city center, besides the signs of the devastation caused by the August explosion are other forms of ruins, which trace back to the Civil War (1975-90), and which are equally charged with political and cultural connotations. A few miles away from the port, in fact, stands the so-called Egg—a ruined concrete shell located in proximity of the famous Martyrs’ Square. Originally designed in 1965 by Lebanese architect Joseph Philippe Karam, the Egg is paradigmatic of Beirut’s current problems, but also of its incredible challenges and opportunities. Its location tells us about the intricate relationship between design, politics and public space. This article describes the Egg for its relevance as sounding board of higher instances, and its appropriation as a political act. The choice of the Egg as ideal place for conversation has crystalized the rise of alternative models of participation and, at the same time, has testified the latent capability of architecture to provide a framework for action. The Egg becomes an amplifier: its interiors absorb and reverberate the need for new demands—either spatial and political.

The Mirror-City.

Alexandre Kazerouni

Read moreOf all the cities that have managed to position their names within the most heavily mediatized representations of the process of globalization underway since the end of the cold war, Abu Dhabi’s narrative is one of the most unexpected. Bucking the already venerable association of Persian Gulf principalities with oil and the armed conflicts it has inflamed—the notorious “Gulf Wars”—the capital of the United Arab Emirates has exploited one of liberalism’s most universal cultural symbols: a museum. Dubbed the Louvre Abu Dhabi, it was planned by the ruling family around 2004 and finally opened to the public in November 2017. Far from contributing to political liberalization, however, the sociological impact of the project reveals that it has contributed to a concentration of power by excluding the local middle class from its implementation [see Kazerouni, Le Miroir des cheikhs, 2017]. The goal of this article is to explore the urban dimensions of this phenomenon, leaving behind the main players involved in the project in order to venture into the city and the landscapes that structure the Louvre Abu Dhabi, including its architectural shell. Strangely, this path does not lead to the modern capital of the United Arab Emirates, which has grown on the island of Abu Dhabi in the twentieth century, but to a mirror-city that extends as far as London, New York, and Paris.

Toward a City of Joy

Laure Ribeiro

Read moreChildren live on the city’s margins: they do not move around unaccompanied and don’t play in the streets but rather in stereotypical, confined spaces that format their way of moving and perceiving. And yet interaction with her environment, and freedom of movement—not to mention the ability to share the same world as his elders—are vital to a child’s full development.

Are the causes of this retreat from the public space of the street linked solely to the child’s risk of being kidnapped or assaulted or of being hit by an automobile? What are the reasons for such obsessive concern over a child’s security? Behind this fear of urban perils that might afflict a child might there not lie an unspoken fear of children themselves, those beings that Aristotle termed “an anomaly”? Is the marginalisation of the city kid not symptom of an overarching rejection of children themselves because of how they embody questioning, openness and freedom?

Autocratic regimes such as Sparta’s advocated for the regimentation of children and their separation from the world. In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley depicted an authoritarian society in which children, produced by machines and conditioned to accept the social class for which they were built, live in a parallel world to that of adults. In contrast to these concepts might not a truly democratic city advocate for the personal growth of a free, independent child, as Janus Korczak or Alexander Neill argued a century ago? Where does a child’s freedom to explore and inhabit a city stand now? And are various initiatives currently aimed at furthering these ideals—notably in Paris—up to the task?

From Articulating the Issues to Formulating the Project

Nathalie Roseau

Read moreDuring the1990s, a certain number of notions were formulated in an attempt to conceptualize the territorial forms of the city emerging in Europe at the time, that is to say, the continuous constellation of urban layers that was spreading over hundreds of kilometers and reinterrogating the notion of the city and dwelling. The Città diffusa, the city-territory, the emerging city, the generic city, Metapolis, the hyperville, the Zwischenstadt: while the Pompidou Center put on a major exhibition about La ville, art et architecture, (The City, Art and Architecture), the journal Le Visiteur contributed to this debate by publishing texts on the contemporary city by Melvin Webber, André Corboz, Bernardo Secchi and Rem Koolhaas. Starting from the principle that the context was not the expansion of cities but a “deepening” of territories, there was a profusion of new terms for the urban phenomenon that sought to capture what the old words could no longer grasp. The birth and dissemination of the vocabulary of the urban must be related to the appearance in the 2000s of a certain number of approaches to large-scale projects that were diverse in nature, and that in turn reinterrogated the contours of the city-territory in which they were inscribed, while operationalizing reflection. From observation to action: after the high points where interests converged; divergences came to the fore and shattered the basis of representation, revealing ambiguities, eliciting controversies, while more discreet trajectories were taking shape. What do these discrepancies and these frictions that are shaping the urban tell us? Formulating the project: along what paths can collective action direct itself in order to define an ecology of the city-territory?

Cubistic, Cubic, and Cubist

Yves-Alain Bois

Read moreIs there a cubist architecture?

Perhaps not. I see nothing cubist, for example, but nothing at all, in Duchamps-Villon’s celebrated Maison Cubiste. And though I have only a very limited knowledge of it, I’d say the same of the so-called “cubist” architecture of Prague.

It is all matter of definition. My definition of cubism is resolutely narrow: it has little to do with the geometrizing style that sent ripples through the entire Western world of art during the teens and developed into art deco a decade later; rather, it is exclusively concerned with the analysis of the conditions of pictorial representation, and their deliberate subversion, carried out by Picasso and Braque. In other words, I cling to the distinction, first established by Danie-Henry Kahnweiler and then further elaborated by John Golding and Edward Fry, between the work of these two artists from 1907 to 1914 and that of all the other painters and sculptors usually placed under the banner of cubism (especially the much-acclaimed “theoreticians” of the “movement” , Gleizes and Metzinger.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.